by Ken Francis

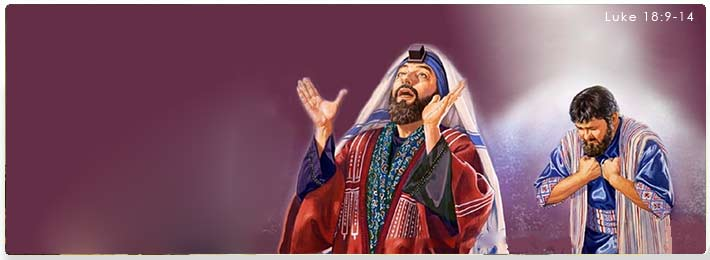

(Based on Luke 18:9-14; Ro 5:1-11)

Can you see it? This scene? This delightful short drama, painted very economically by Jesus …

I doubt he meant it as comedy, but to me it seems so comical! Like a cartoon. We could almost do it as a little drama … a bit of street theatre:

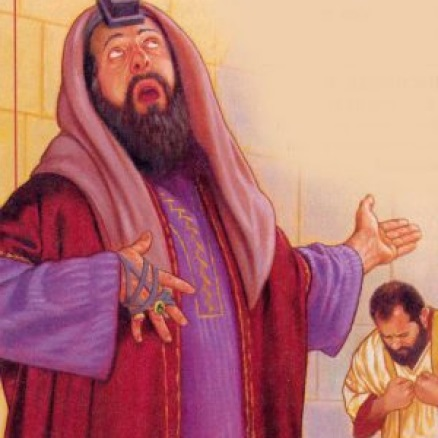

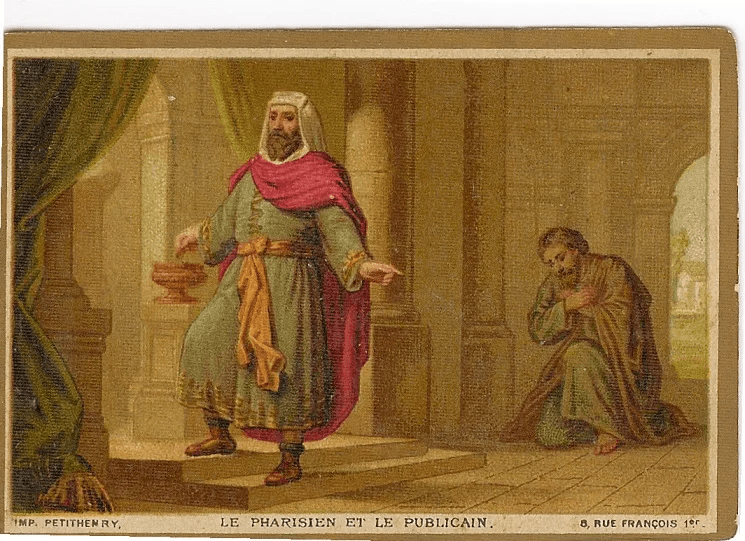

There on your left stands a proud, dignified looking man, pompous and cartoonish, head held high and sneering sideways, telling God how righteous he is! Not like that sinner over there.

On your right, a bowed, cowed man, kneeling, too ashamed to come near the altar, even to look up, but deeply contrite. All but sweeping handfuls of ashes over himself.

This second guy – the King James Version calls him a ‘publican’ (which, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica, was the label given to an “ancient Roman public contractor”), and seems to be, in Jesus’s telling, a tax collector – is hardly a cartoon though. That wouldn’t do him justice, poor man. But the question is, as we look at these two guys, which one is you?

Which one do you identify with?

Or, let’s say … if he is at one end of the continuum and he’s at the other, and you were asked to position yourself somewhere between the two, to indicate your disposition, where would you stand?

I’m ashamed to say that I’d be much closer to the Pharisee than the publican.

Because the inclination of my heart is to think I’m pretty good. I pay my tithe – I pay my taxes – I try to think of others, I … I’ve never murdered anyone – honest! I never – well, hardly ever – tell lies … or miss church on Sunday. Yes, God I’m pretty good. Thank you that I’m so righteous! Not like all those sinners … out there! Actually, I’m so pleased with myself, it’s hard to be humble. I’m proud of my humility! Like the old saying, I used to be conceited, but now I’m perfect!

But, where would you stand?

And … which of these two guys is the greatest sinner, do you think?

I suggest that they’re both equal sinners. Because, is any one sin greater or worse than another? Was Adolph Hitler any worse than … Queen Elizabeth? We humans – we’re the ones who rank sin. We’re the ones who say genocide is worse than … lying; or murder is worse than … theft. But in God’s eyes, sin is sin. It’s not ranked.

And, don’t forget, there is good in the worst of sinners, just as there’s sin in the best of us … so, let no one cast stones at anyone else, right?

In fact, what is sin?

Judaism regards the violation of any of the 613 commandments as a sin! (We’re left to guess which of the 613 the publican had breached. He was loathed, of course, as a tax collector.)

Well, we’re not Jews, so …

Here are three slightly different views of sin:

In one sense it’s things we do. Our sinful acts, our sinful behaviour. Breaking the rules! The Ten Commandments list some of them. Murder, theft, adultery, coveting. Things we actually commit.

A second way of understanding sin is this: Sin is turning away from God’s purposes, from his call on our lives. (Like sheep, we have all gone astray, wrote Isaiah.) So, when we abuse someone, when we deny someone mercy or justice, when we watch or read something we shouldn’t, when we assassinate someone’s character, when we fail in some way to love our neighbour … we are turning away from God’s purposes. That’s sin. There are sins of omission, of course, just as there are sins of commission.

In another, perhaps even more telling sense, sin is who we are. It is embedded in our very nature. The human condition. We were born sinful, it says in Psalm 51; Jeremiah says the hearts of people are desperately wicked. [Jer 17:9: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it?”] Many think humanity is inherently good, but … can we honestly say that?

St. Augustine said sin is “a word, deed, or desire in opposition to the eternal law of God.” And therefore, needs to be redeemed (that’s a metaphor for paying for someone’s release or deliverance): the death of Jesus is the price that is paid to release the faithful from the bondage of sin.

So, I put it to you that these two men are equally sinful, but … it’s their attitudes that truly distinguish them. One of them (the Pharisee), like me, says, how good I am, that I am not like other men. But the other, the publican – also like me – says, woe is me for I am a sinner. God, forgive me. God, save me. For if he doesn’t, I am lost.

Commentator Matthew Henry writes, “God sees with what disposition and design people come to him. The Pharisee seemed to be a good man, in some respects. But he was boastful, in apparent expectation that God would affirm him, admire him, be in his debt! Moreover, he thought meanly of others, particularly of the publican. The Pharisee claims merit; the publican mercy.” That is the difference that Jesus was emphasising. The difference between the self-righteous and the mercy-seeker. The publican’s disposition is, “Justice condemns me; nothing but mercy will save me.”

We all need to acknowledge this same truth. No matter how good we try to be, it is only through God’s grace, through what Jesus did for us on the cross, that we can have eternal hope. It’s important to recognise this, acknowledge it consciously, confess our sinful nature to him, and cast ourselves on his mercy, like our brother there (the penitent). It’s kind of taking responsibility for who we are in our hearts.

This reminds me of how, as a school teacher, I sometimes found myself having to get to the bottom of teenage conflicts of various kinds, and meting out disciplinary consequences. I might ask some antagonist what happened, and they’d start saying something like, “Well, he tripped me” or “she stole my homework”, or …

Typically, I’d interrupt with, “Ok, but what did you do?” They might say, “Well, I wouldn’t have … if they hadn’t …” And again I’d say, “But what did you do?”

It was commonly difficult to get an adolescent to own his or her own actions – to take some responsibility for what had happened!

The publican was accepting responsibility for his sinful behaviour or nature.

Yes, we are all equally guilty. But it would be a mistake to hold all of this in a solely negative light. At the end of this brief street theatre, Jesus sums up with God’s view of all this. Both of these men are sinners, but only one is “justified”, he concludes. That’s the word he uses, not me. We cannot shed our sinful nature, but we can be confident of being justified if our attitude is right. The Romans reading talked about justification. Martin Luther joyously latched onto the idea of justification at the outset of the Reformation. He described the concept of justification as “just as if I’d never sinned”, which is cute, but actually a very helpful way of thinking of it. “Just as if I’d never sinned.”

All our own righteousness “is as filthy rags” (the prophet Isaiah says), but if we turn to God, we can be ‘counted’ righteous, it says in Romans. We take upon ourselves His righteousness – Jesus’s righteousness. Yeah?

The words righteous and righteousness – we don’t use them much in modern parlance – we use the word ‘sin’ even less – actually occur 72 times in Romans! Ro 4:5 says: “to the one who … trusts God who justifies the ungodly, their faith is credited as righteousness.”

We can’t tell God about how righteous we are! Like this guy. How arrogant. God laughs. But He credits us as righteous, if we come to him as the publican did.

A delightful little parable. Spoken, it says in verse 9, to some who were “confident of their own righteousness and looked down on everyone else”. Actually, it’s not a parable at all – a parable is a superficial story with a deeper meaning. This is a straight out narrative of what’s what around approaching God. A contrast between how to be and how not to be.

Friends, let’s get closer to the publican’s end of the spectrum …

Concluding prayer:

Father, help us to see merit in the publican’s approach to your throne. Help us to find humility as we approach, and true regret for our sinful inclinations. Then to receive, by faith your credit of righteousness, based on what you have done, not on our own efforts. Then to find true gratitude, that you have taken the initiative to rescue us from whatever sin has made us. We are enormously grateful even this morning as we reflect on these things.

Help us to walk our walk this week, with intent and integrity, and may our walk of faith please you. Amen